This paper is the review of Phonon coherences reveal the polaronic character of excitons in two-dimensional lead halide perovskites, which is written by Thouin, F., Valverde-Chávez, D.A., Quarti, C. et al. on Nature Materials. 18, 349–356 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-018-0262-7

Introduction

Hybrid organic-inorganic metal halide perovskites have become an interesting area in materials science owing to their unique optical and electronic characteristics, and have been widely used in the preparation of optoelectronic devices such as solar cells[1]. The distinct lattice structures of these quantum well-like derivatives result in unique behaviour. To elucidate the peculiar nature of these materials, Félix Thouin and his colleagues delve into the interaction between excitons and phonons in 2D lead halide perovskites, providing significant insights into their polaronic nature and the resultant impact on their optoelectronic properties in the paper I reviewed, which confer both structural flexibility and remarkable electronic characteristics. This review will offer a detailed discussion of the computational and experimental results presented in their publication, alongside a broader introduction to the topic. In two-dimensional lead halide perovskites, strongly bound, stable excitons typically exist at room temperature within the lattice and exhibit lower binding energies[2]. These lower binding energies result in the coexistence of multiple excitons with distinct lattice couplings, introducing dynamic disorder effects. Such unique coupling facilitates the formation of biexcitons, which has profound implications for developing light-emitting devices. What distinguishes these excitons from those in non-ionic semiconductor quantum wells is their rich spectral structure, which depends on the degree of lattice distortion imposed by the organic cationic ligands. To differentiate various excitons, the reviewed paper implemented high-resolution resonant impulsive stimulated Raman spectroscopy (RISRS)[3][4], as resonance Raman spectroscopy serves as a direct optical probe of polaronic effects on the nature of excitons[5].

Exciton

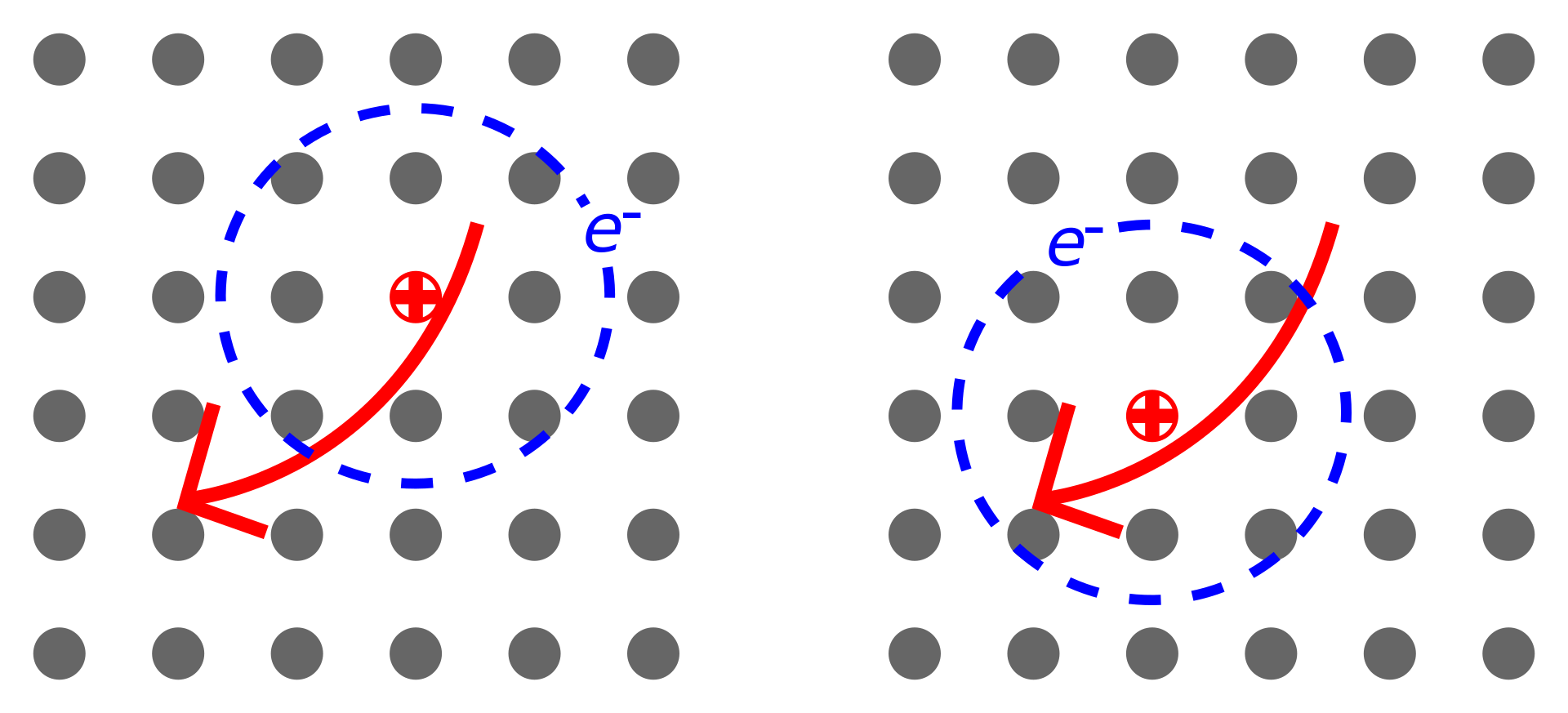

An exciton is a type of bound state formed by an electron and an electron hole, attracted to each other by the Coulomb force[6]. This exciton can transport energy without carrying a net electric charge, making it an elementary excitation. Excitons are commonly found in condensed matter systems such as insulators, semiconductors, and some metals. However, electrically neutral quasiparticles like excitons can also be found in certain atoms, molecules, and liquids.[7]

When discussing electrons and electron holes, we must consider band theory and energy relations. When photons are absorbed by a material, the excited electrons are promoted to the conduction band, creating holes in the valence band. Unlike the typical electron-hole pair model, in the case we are discussing, the electrons and holes are located at the same or adjacent positions in the lattice[9]. This proximity allows them to form a bound state through Coulomb interaction, which can be regarded as a composite quasiparticle. From a definitional perspective, excitons can also be considered composite bosons formed by two fermions, the electron and the hole. This bound state results in excitons being electrically neutral, but they can move through the lattice with the aid of band theory, just like the schematic shown above. Thus, excitons can traverse the lattice, transporting energy without any net charge transfer, which in turn causes the wonderful photoelectric properties we observe on a macroscopic scale. Because excitons are composite bosons, they can interact with light. When excitons absorb, reflect, or transmit light, they generate narrow spectral lines in the spectrum. As previously mentioned, an important condition for the formation of excitons is that the electron-hole pairs are located at the same or adjacent positions in the lattice. Thus, the energy of their narrow spectral lines is lower than the free particle band gap of insulators or semiconductors. This phenomenon provides the theoretical basis for the spectral analysis of excitons discussed in the paper[10].

Phonon

Just as photons are quantized electromagnetic waves, phonons are quantized mechanical waves[11]. In a crystal, atoms or molecules are arranged in a uniform, repeating structure. These atomic arrangements are not static; they undergo thermal vibrations due to heat, causing the atoms to oscillate at specific frequencies. In this vibrational mode, the interaction (bond) between atoms in the crystal can be imagined as behaving like a spring in the macroscopic world. This interaction generates mechanical waves within the lattice, which traverse the lattice with specific momentum and energy. Due to the wave-particle duality in quantum theory, phonons, though wave-like phenomena, can be regarded as particles with discrete vibrational energies in the field of microscopic condensed matter physics. This treatment is similar to how photons are considered particles arising from electromagnetic waves. However, unlike photons, phonons of different wavelengths can interact and mix when they collide with each other, similar to how mechanical waves behave in the macroscopic world, resulting in the formation of different wavelengths. This interaction leads to chaotic behavior, making the prediction and control of phonons more challenging. Just as photons of a given frequency can only exist at specific energy levels, phonons can also be described by band structure diagrams[12]. Phonons can be represented on a graph showing energy (in terms of frequency ω) against momentum (k), revealing two bands separated by a phonon band gap. These bands consist of a higher-energy optical band and a lower-energy acoustic band. Additionally, the distinction between longitudinal modes (where vibrations align with phonon propagation) and transverse modes (where vibrations are perpendicular to phonon propagation) is determined by the direction in which the vibrations and phonons travel.

Materials

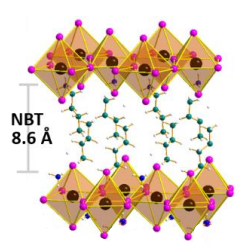

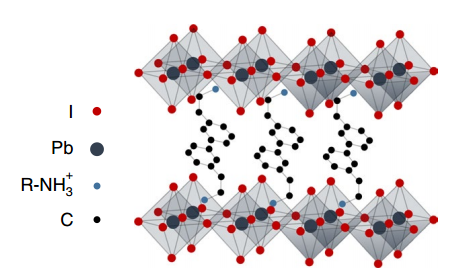

In the reviewed paper, two prototypical single-layer perovskite systems, (PEA)2PbI4 (PEA is the abbreviation of phenylethylammonium) and (NBT)2PbI4 (NBT=n-butylammonium) are mainly focused on. Their structure is shown in the figure below. Perovskite crystals can form a cage structure. In the two materials selected, the inorganic framework consists of lead iodide octahedra, which form a network through corner-sharing. Large organic spacer cations are sandwiched in the middle to create a natural multi-quantum well structure, where the inorganic plate layer acts as a potential energy “well” and the organic layer serves as a potential energy “barrier”[13].

It is precisely because of this unique structural feature that the Pb-I framework can be deformed under interaction, altering the inorganic cage structure and distorting the structure of the entire inorganic lattice. This structural change induces significant dynamic disorder in the lattice, facilitating interactions between electrons and phonons, which in turn modifies the material’s physical properties. Such distortion plays a key role in carrier localization and subsequent broadband emission[14].The effect of the interaction between excitons and phonons, resulting from the changes in the spatial structure of the crystal, is precisely what the reviewed article aims to study. This type of 2D perovskite exhibits excellent optoelectronic properties. Experiments show that it typically presents an extremely narrow-band photoluminescence (PL) spectrum with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of only about 25 nm. From the structural schematic, it is evident that two organic amino linkers connect different inorganic layers, guiding the crystal to grow in a non-oriented manner to form a spatial crystal structure. Among these, (NBT)2PbI4 has an orthorhombic structure with a <100> orientation[14]. The variable spatial structural characteristics of 2D perovskites also introduce challenges. During crystal growth or thin film application, potential spatial orientation disorder and lattice strain can lead to defects, affecting the generation and characteristics of excitons or carriers, as well as the optoelectronic properties of the entire material. This poses an obstacle to the large-scale preparation of such materials. Additionally, the organic long-chain structure between the layers can impact the transmission of interlayer charges, necessitating careful design of the interlayer organic molecular chains[13].

Methodology

To study the interaction between phonons and excitons in two-dimensional perovskites, the original article primarily employed a research method that combines theoretical calculations with experimental analysis. The research team used the Density Functional Theory (DFT) algorithm to calculate and analyze the possible frequencies, and then conducted measurement experiments using Resonant Impulsive Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy (RISRS). By comparing the results from these two approaches, they were able to draw conclusions. This section will briefly introduce the two methods used in the study.

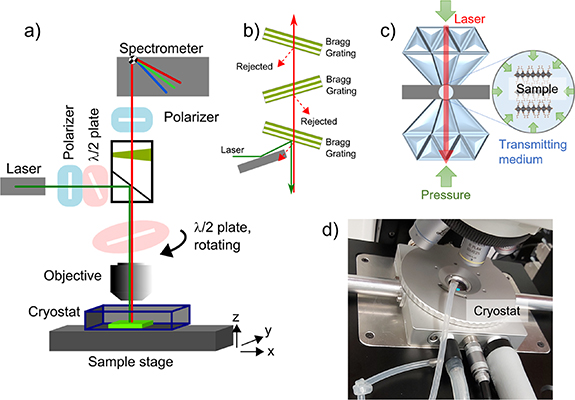

Resonant Impulsive Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy (RISRS)

The core of Raman spectroscopy lies in its interaction with excitons. As an inelastic light scattering effect, incident photons can lose (or gain) energy by interacting with excitons in the material. Monochromatic excitation light interacts with electrons in the material, producing inelastic scattering, and the polarizability changes due to vibration. Thus, the phonon mode will appear in the scattering spectrum at a wavelength different from the excitation wavelength. The difference between the phonon mode and the excitation wavelength, known as the “Raman Shift”, represents the energy difference between the phonon-scattered light and the expected luminescence. This shift is the core measurement content of Raman spectroscopy, expressed in units of inverse centimeters (cm−1)[16]

In specific measurement and analysis, the intensity of Raman scattering is influenced by the polarization states of incident and scattered light. These polarization states are determined by the orientation and symmetry of the molecules and atoms in the crystal, which are guided by the direction of chemical bonds. Therefore, RISRS provides excellent spatial resolution and can effectively analyze the orientation and symmetry of the crystal. Additionally, Raman scattering can differentiate between the inorganic and organic parts of the crystal in a qualitative description. Since the atomic composition of organic components is significantly different from that of inorganic components[17], and typically has a smaller relative atomic mass, the Raman shift of their vibration modes will be larger compared to the heavier inorganic parts[18]. This charac teristic makes Raman scattering particularly be able to identify chemical bonds in functional groups. Based on the above reasons, for the 2D perovskite materials discussed in the original article, which feature both long organic interlayer chains and inorganic symmetrical polyhedral structures, RISRS can be regarded as a highly effective research tool. It not only quickly captures high-resolution spectra but also directly observes the coupling between excitons and phonons.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

If we describe Density Functional Theory (DFT) in detail, it would probably take another paper. Let me briefly talk about its development history. Its predecessor was the Thomas-Fermi model, independently developed by Llewellyn Thomas and Enrico Fermi in 1927[19]. They used statistical models to approximate the distribution of electrons in atoms. This idea can be traced back to the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem[20], which states that the ground state properties of a multi-electron system are uniquely determined by the electron density, which depends only on three spatial coordinates. This approach allows us to simplify the many-body problem of N electrons in 3N spatial coordinates by using a functional based on electron density, reducing it to a problem involving only 3 spatial coordinates. From the perspective of a complex definition, Density Functional Theory (DFT) attempts to ad dress the inaccuracies of high frequencies and the high computational requirements of post-high frequency methods by replacing multi-body electron wave functions with electron density as the fundamental quantity[21]. Intuitively, this method provides a modeling analysis of complex elec tronic systems under quantum mechanical conditions. In the original article, DFT calculations were used to simulate the vibrational modes of the perovskite lattice. These calculations en abled the research team to assign the observed vibrational frequencies to specific lattice modes, thereby helping to better understand the RISRS spectra introduced in the previous section.

Results and Discussion

Exciton absorption

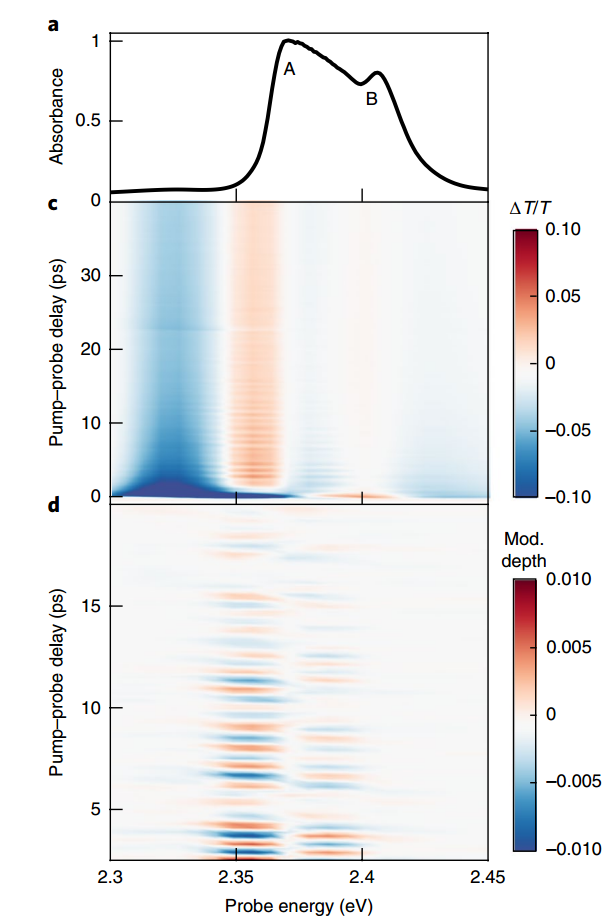

The figure above shows the exciton absorption spectrum of (PEA)2PbI4. The Figure.4a represents its exciton absorption spectrum at 5K. We can clearly observe two main transition peaks at 2.37 eV and 2.41 eV. Then, transient absorption measurements were performed by pumping 3.06 eV into the conduction band, obtaining the time-resolved differential transmission spectrum shown in Figure.4c and the time-resolved differential transmission spectrum of the oscillating component shown in Figure.4d. The oscillatory component of the differential transmission signal arises from the Raman interac tion in RISRS. When the duration induced by the ultrashort pump pulse is much shorter than the period of the Raman-active low-frequency vibration, the pulse force generated by the Raman interaction drives coherent motion within the lattice. This motion modulates the dielectric con stant at the lattice motion frequency, thereby forming a spectrum of varying intensities in the image. We can observe different positive and negative features in segments A and B, indicating the displacement and transition of excitons. The increase in the intensity of the positive signal compared to the ground state suggests that the carriers are being converted into excitons. The reason for choosing 5K here is that the coherent oscillation caused by phonon-phonon scattering at higher temperatures dephases more rapidly, resulting in a reduced modulation depth. Additionally, because the exciton spectral structure persists below room temperature, we focus on measurements at 5K to obtain more pronounced results.

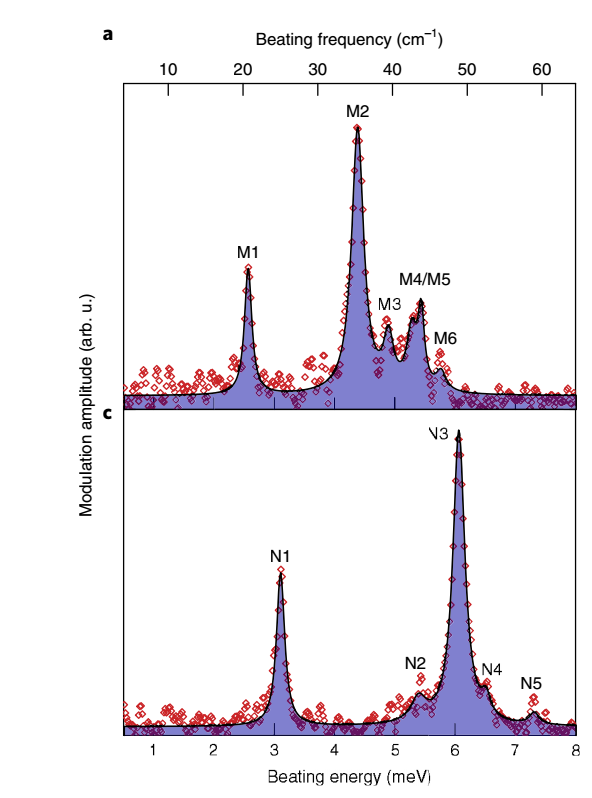

Also for the (NBT)2PbI4, they also get the RISRS spectrum at 3.06eV as the above Figure.5c shown. By doing DFT to calculate the vibrational normal modes of these two materials and comparing these with the experimental vibrational frequencies, remarkably consistent results were found between the theoretical predictions and the experimental data. However, compared with (PEA)2PbI4, the spectrum of (NBT)2PbI4 shows that all its exciton modes appear to shift to higher energy. It is speculated that this shift may be due to lattice hardening caused by octahedral distortion prevalent in its low-temperature phase. This shift reflects the changes in optoelectronic properties caused by crystal lattice distortion, as mentioned in the material introduction section above.

Phonon coherence

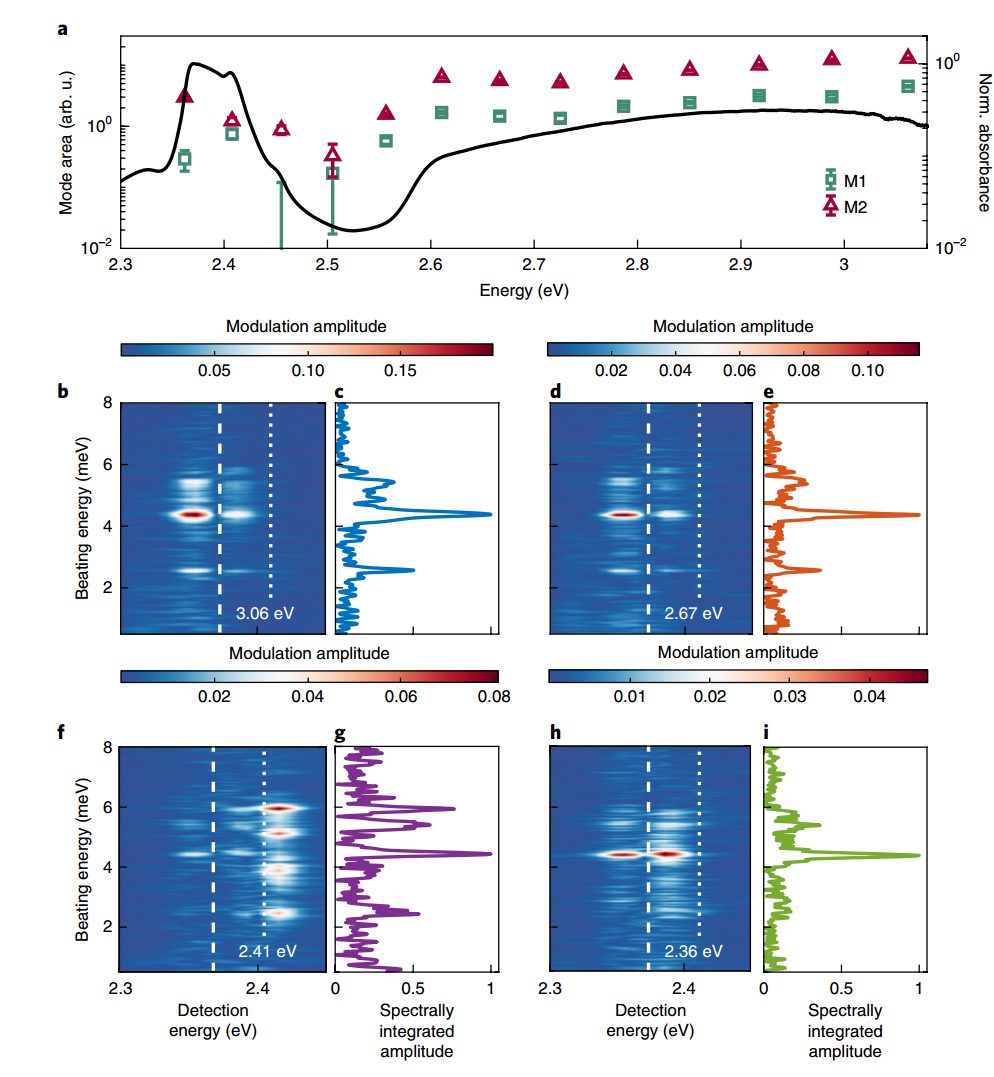

To analyze the coherence of excitons and phonons, we first start from the two most intense lattice modes, A and B, in material A. We find that when the pump energy is ≥ 2.56 eV, the intensity of the two modes in the excitation spectrum increases monotonically. Then the original paper describes pumping continuum 3.06 eV and 2.67 eV to obtain Fig.6(b,c)(d,e), respectively. Additionally, 2.31 eV and 2.46 eV were used as two pump inputs corresponding to different exciton energies A and B , get the Fig.6(h,i)(f,g).

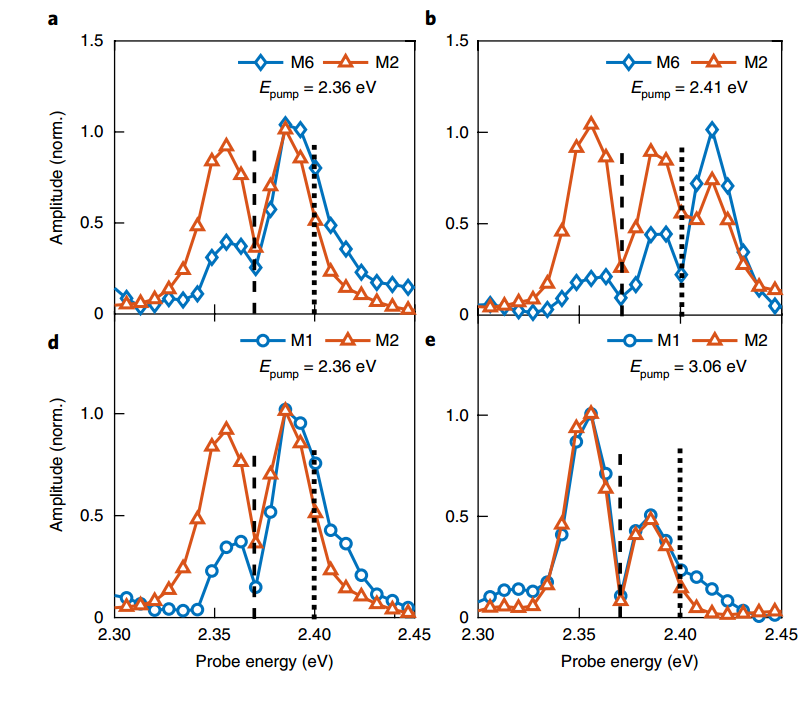

We can observe from the figure that different exciton energies have different coupling strengths for various lattice modes. For example, exciton A shows strong coupling to mode M2, indicating that each exciton state has distinct lattice coupling characteristics. The varying amplitude values exhibited by different lattice modes at different exciton pump energies(Fig.7) further support this conclusion.

Conclusion

We already know the importance of two-dimensional perovskite materials for optoelectronic devices such as light-emitting diodes or solar cells. However, the development of these materials is currently hindered by the complex and unclear interactions between the spatial structure of the crystal and phonons and excitons. This article proposes a possible interaction behavior mode between phonons and excitons in two-dimensional perovskite materials. The specific coupling between excitons and phonons may be crucial for future control of exciton behavior in these materials, thereby effectively improving the efficiency of related optoelectronic devices. The conclusion drawn in the article is that excitons in two-dimensional perovskite materials can couple with the phonon modes inherent in the crystal structure. This suggests a theoretical possibility of controlling exciton behavior mechanisms through the phonon properties of the material itself. More importantly, the experimental method used in the article. RISRS (Resonant Impulsive Stimulated Raman Scattering), successfully obtained the absorption spectrum of the material to analyze the possible energy states of excitons. The phonon modes of the crystal were then calculated using Density Functional Theory (DFT). The experimental results showed a high degree of consistency between the RISRS measurements and the DFT calculations, proving the reliability of this methodology. This provides a feasible solution for future research on phonon exciton interaction in other two-dimensional materials in the field of optoelectronics.

References

[1] Khagendra P Bhandari and Randy J Ellingson. “An overview of hybrid organic–inorganic metal halide perovskite solar cells”. In: A Comprehensive Guide to Solar Energy Systems (2018), pp. 233–254.

[2] Teruya Ishihara, Jun Takahashi, and Takenari Goto. “Exciton state in two-dimensional perovskite semiconductor (C10H21NH3) 2PbI4”. In: Solid state communications 69.9 (1989), pp. 933–936.

[3] Lisa Dhar, John A Rogers, and Keith A Nelson. “Time-resolved vibrational spectroscopy in the impulsive limit”. In: Chemical Reviews 94.1 (1994), pp. 157–193.

[4] R Merlin. “Generating coherent THz phonons with light pulses”. In: Solid state commu nications 102.2-3 (1997), pp. 207–220.

[5] AK Sood et al. “Resonance Raman scattering by confined LO and TO phonons in GaAs AlAs superlattices”. In: Physical review letters 54.19 (1985), p. 2111.

[6] ThomasMuellerandErminMalic.“Exciton physics and device application of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductors”. In: npj 2D Materials and Applications 2.1 (2018), p. 29.

[7] Monique Combescot and Shiue-Yuan Shiau. Excitons and Cooper pairs: two composite bosons in many-body physics. Oxford University Press, 2015.

[8] Wikipedia contributors. Exciton. en. June 2024. url: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Exciton.

[9] Jacov Frenkel. “On the transformation of light into heat in solids. I”. In: Physical Review 37.1 (1931), p. 17.

[10] Ashish Arora. “Magneto-optics of layered two-dimensional semiconductors and heterostruc tures: Progress and prospects”. In: Journal of Applied Physics 129.12 (2021).

[11] Steven M Girvin and Kun Yang. Modern condensed matter physics. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

[12] Prasanta Kumar Misra. “§ 2.1. 3 Normal modes of a one-dimensional chain with a basis”. In: Physics of Condensed Matter; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA (2010), p. 44.

[13] Yani Chen et al. “2D Ruddlesden–Popper perovskites for optoelectronics”. In: Advanced Materials 30.2 (2018), p. 1703487.

[14] Daniele Cortecchia et al. “Broadband emission in two-dimensional hybrid perovskites: the role of structural deformation”. In: Journal of the American Chemical Society 139.1 (2017), pp. 39–42.

[15] F´ elix Thouin et al. “Phonon coherences reveal the polaronic character of excitons in two dimensional lead halide perovskites”. In: Nature materials 18.4 (2019), pp. 349–356.

[16] Davide Spirito et al. “Raman spectroscopy in layered hybrid organic-inorganic metal halide perovskites”. In: Journal of Physics: Materials 5.3 (2022), p. 034004.

[17] Bernhard Schrader. “Chemical applications of Raman spectroscopy”. In: Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 12.11 (1973), pp. 884–908.

[18] Feliciano Giustino and Henry J Snaith. “Toward lead-free perovskite solar cells”. In: ACS Energy Letters 1.6 (2016), pp. 1233–1240.

[19] R. Parr and W.Yang. Density-functional theory of atoms and molecules. Oxford University Press, 1989.

[20] Pierre Hohenberg and Walter Kohn. “Inhomogeneous electron gas”. In: Physical review 136.3B (1964), B864.

[21] Maylis Orio, Dimitrios A Pantazis, and Frank Neese. “Density functional theory”. In: Photosynthesis research 102 (2009), pp. 443–453.